Making the world less real makes us less human

How playing at the simulated world could help us get our humanity back

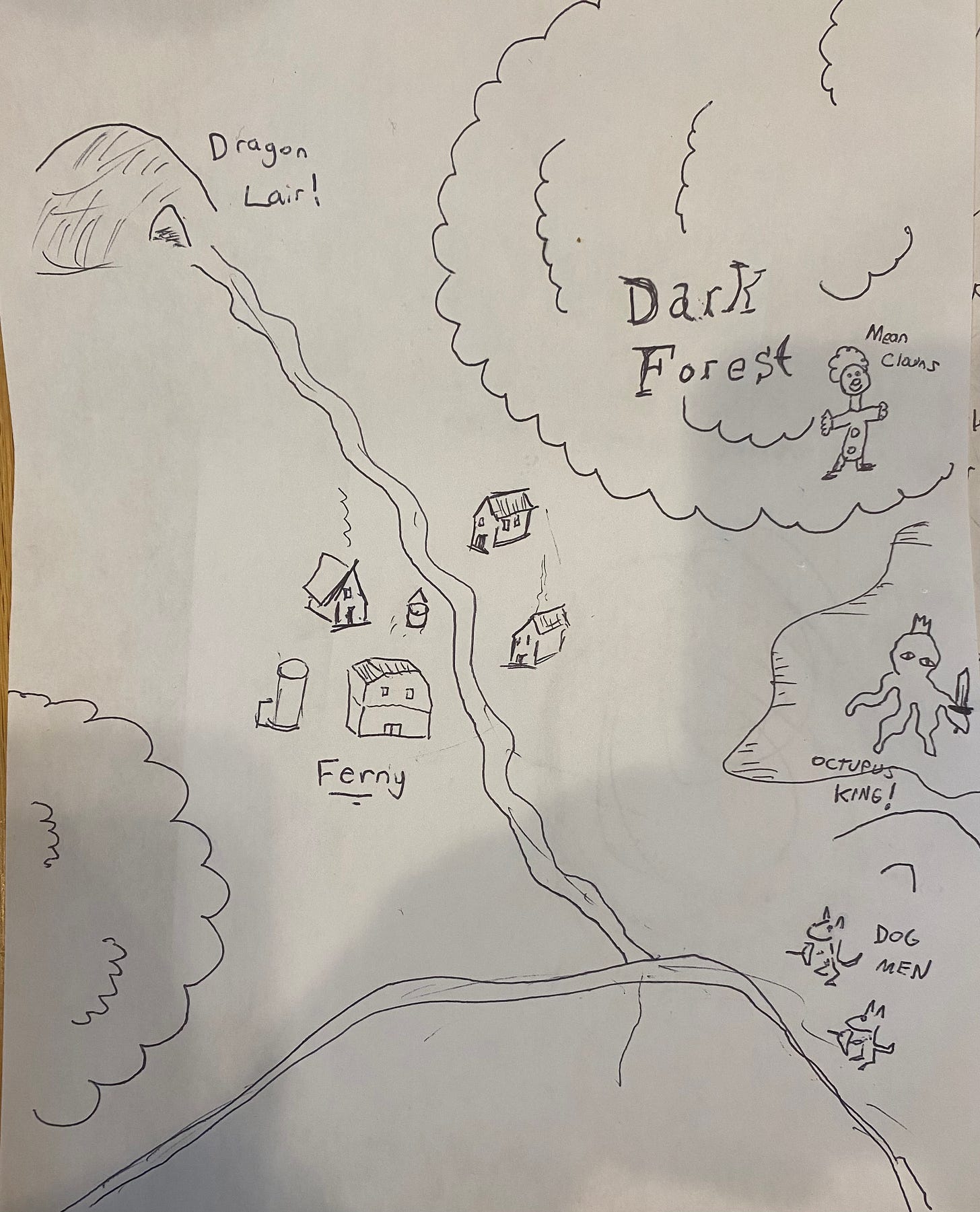

For the last year or so I’ve been playing D&D / RPGs with my 3 year old daughter. She calls them “the map game” or “the floor game” because we usually take a big map and play on the floor, or we draw maps on the floor together.

In that time, an interesting thing has arisen about what we are trying to do and how it works. It can work just like HG Wells’ floor game with his kids and we do that sometimes. We create a situation and then we take turns saying what happens next (obviously inspired by Story Games Sojourn ).

That has been a lot of fun, but the adventure game is definitely lost. As I discussed with Sam, you definitely cannot do both things at the same time, you have to decide if you can say “no” because only the Referee knows there is a secret spell for the magic door, which must be found on the map. Playing with my daughter has made even more clear things about agency, choice and constraints in the fiction.

As time has gone on, those two things have become two different games. Sometimes we play “the story game” and she knows she can say what happens next. Sometimes she plays “the adventure game” and she needs to explore the map to find what she needs. It is often as simple as this:

“A story game means I get to say what happens and what’s behind the door.”

“An adventure game means Daddy keeps what’s behind the door a secret, and I get to choose what to do.”

Being able to allow the imagination to fly unbound in a collaboration is certainly a good thing and we enjoy it, but there’s something about creating constraints. It has something to do with the real and being human.

I believe I tend to see that tabletop discourse lacks those two things, and I think it’s part of why the mainstream product is in such a poor state. It is less human, and less real. It has to do with this hatred of the material, of the flesh, the pain, the complexity, the ugliness of human life. It’s more a hatred of the real than any real commitment to believing there can’t be anything real, though in the discourse you’d think the latter might be the case.

There’s especially something about the dungeon. I reintroduced it again the other day to my Daughter, the “underworld” I call it. She hated it. After 3 rooms, and her friend nearly dying in a pit, she said she’d rather not adventure in the underworld any further. Being in the mode of adventure gaming, I said “Of course! You can adventure in the world above if you like” and she was amicable to that. An adventure game is about choice in the context of a sub-created reality. There can be no choice without a reality.

Then, for the next two days, it bothers her. She’s obsessed. She talks about the underworld constantly. She explains to Mamaw how she thinks the underworld works and what’s down there. She thinks of monsters and treasure. I’ve seen this happen with tiny people and very old people. It strikes something. Hell does that.

That doesn’t mean she “likes” the underworld, she doesn’t think it’s “cool”, but there’s something in her that has to deal with it, even at 3.

In story games, she gets to say what happens next. Being 3, the story flies apart, loses all sacred pattern, she introduces silly and wild elements which crash the world and it loses anything both real and awful. She would want no dungeon in her story game, thank you. The dragons are nice, in the story game. I find that I often have to help host the story game for her in order for it to contain meaning and for the story to continue, though I’m learning right along with her.

In the adventure-map-game, she cannot flit to the other side of the map out of curiosity on a suddenly appearing airplane.

“No you have to travel there. It will take time. It’s cold, do you have a coat?”

She didn’t have one, she spent all her money recently on a pink boat.

“Then you are cold.”

I narrate the terrible cold in Dolmenwood. Winter has come, so the calendar and it’s weather tables say. She shivers and asks me why it’s cold in the house (it isn’t). Her single NPC henchman (mouse-friend) gives his shirt (I take off my hoodie and give it to her in real life). He shivers. She is sad. They need money for winter clothes for their adventure to discover what is happening in a nearby dark wood.

None of that comes from my caprice, my choice, my design. It comes from a map, weather tables, physics, distances, diegetic objects which are “there” in that sub-created world. The towns have items, an economy, travel takes time, distance, effort.

The difference is that the voice of God cannot come from me. It must be approached reverently, snuck up on, treated like a gentlemen, invited. Of course the sub-created world is a fantastical place, and of course it is also a place of possibility. But it is also a place of the real and the true. And that means pain.

To put it differently, the actual world is not merely distance, rate, time, temperature, and weight either. Much like the sub-created world it also has observers, points of view and even powerful things which peer back at the observer. However, the real world contains it’s mountains which the human body must endure, and as such, the mountains can help show us we are human. And so, the sub-created world must also have mountains, with streams that flow a certain way...

In adventure games the world says “no.” You die. The dragons are not nice. The underworld cannot be escaped. And weirdly, that’s exactly what allows someone to really choose something.

Lethality and pain is consequence. Consequence means choice is possible.

The underworld above all, makes a real choice possible, and a real choice lets us be human for a little while. It doesn’t make it pretty, or cool, or satisfying, but the honesty of the underworld is a form of reprieve, not from the real, but the unreal we are constantly surrounded by. The unreal, and inhuman.

Paradoxically, being a dwarf in a dungeon of monsters gives us a chance to experience the real, and the human. (As long as we track the Dwarf’s encumbrance.)

Richard Chase says, that this quality of story found in folk tales cannot be seized, it must be snuck up on, as if shyly.

“And what of the creative use of our folk traditions? ‘Great Art’ wrote John Jay Chapman, ‘does not come on call, and when it comes it is always shy.’

and also

“A true folk singer sings ‘by the heart’ and not out out of books. He never tries to impress an audience, because at his best he is a real artist. Sincerely he shares his love and knowledge of these things with you rather than performing them for you. He sings ‘ unthoughtedly,’ without self-consciousness. He makes his points without overdoing! He never shows his tonsils! Folk arts lose their magic the instant they are exploited sensationally.”

-American Folk Tales and Songs - Richard Chase

This element “outside the world” that is not necessarily the story, but it’s seed, and not driven “by the purposed domination” of the host or leader of the experience, is also not God, but we could hope to invite Him perhaps.

And even then, we maybe shouldn’t declare it so when we think we’ve got a grasp on that, but allow ourselves to be surprised, or disturbed, or to simply see. Or if we see nothing at all there, then maybe that is something too.

They survived their trip on the pink boat in the cold and completed the quest for the Knight. My daughter smiled with a new confidence, because she knew it was not just a contrivance that did the Quest of a Knight of Brockenwold, she did not simply declare it to be so, but a sub-created thing held with an honest and open palm, which could be cold, and even die.

These however, are the perilous realms. And we do not know if they will survive next time. It is not possible for me to know, since I aim as best I can to approach the tale “unthoughtedly.”

Excellent post. You put into words much of the ideas I've discovered over the last dozen years or so (and attempted to convey), this difference between imaginative play (story creation...what my young daughter used to call "D&D 3" with no relation to 3E) and experiential gaming (standard, rule-driven D&D). Both have value, but they are two very different things.

A topic articulating concerns I've long had about TTRPGs. Too much power creep. Too many easy wins. I liked DnD from the 1970s; one had to garner much experience to make the next level. One *earned* it.

Later, I took to Runequest III. It has about the best combat system yet devised, made by persons experienced in SCA combat.

I've yet to find a magic system worth a hoot. Magic is a metaphor for madness; a little crazy goes a long, long way. Too much magic makes a game suffer badly, particularly when spells are stripped of dire consequences/costs for their use. (Looking at you CoC version VII)

God is infinite; God made man all He is not. The one thing He is not is *limited.*

In our constraints and limitations, we find all meaning. As it must be.