The Monsters Don't Know What they are Doing

Monsters have their own agenda apart from the existence of the player characters

Illustration from Basic Fantasy Roleplaying Game: https://www.basicfantasy.org/

In October of 2019 Keith Ammann published his popular book titled “The Monster’s Know What They are Doing - Combat Tactics for Dungeon Masters” based on years of blogging and advice. According to Keith, the premise of the blog was to look at monsters as “professional monsters.” They would likely act like professional Soldiers, carefully having prepared their moves and tactics in advance, rehearsed and executed them countless times. The Monsters would “know what to do” to emphasize their strengths and the character’s weaknesses when making contact in combat.

“The way to avoid this is to make as many of these decisions as possible before the session begins, just as a trained soldier—or accomplished athlete or musician—relies on reflexes developed from thousands of hours of training and practice, and just as an animal acts from evolved instinct. A lion doesn’t wait until the moment after it first spots a herd of tasty gazelles to consider how one goes about nabbing one, a soldier doesn’t whip out his field manual for the first time when he’s already under fire, and a DM shouldn’t be deciding how bullywugs move and fight when the PCs have just encountered 12 of them.”

-Keith Ammann - “About This Blog” Aug 2016 https://www.themonstersknow.com/about/

This blog and it’s subsequent book were seen as many in the 5e space as a kind of “revolution” to approaching monsters. Certainly, it’s much more interesting than what I call a “stabbing zoo” where monsters sit idly waiting for characters to come by and then rush to charge them with basic abilities and numbers like trash mobs in a multiplayer online video game.

It also helps answer one of the design flaws of Dungeons and Dragons Fifth Edition: the game is utterly unhelpful in providing the necessary “balance” for satsifying combat, which is the main focus of that game’s rules. At the same time, it’s also very difficult to continue to challenge players in Dungeons and Dragons Fifth Edition over time as they level and gain power.

From the perspective of the Old School Renaissance, one might also be sympathetic to the idea that monsters would be prepared to expertly apply their strengths on the player characters point of utmost weakness. Old School games are about player challenge and skill over gameplay abilities right? The OSR is lethal, right?

If you’ve seen my post on “The Myth of OSR Lethality” you probably already know my take on that. No, monsters awaiting player characters with a borderline meta-knowledge of them is not commensurate with the OSR style of play in my opinion, and in fact, is contrary to it. This is because it undermines the truth of the world, the potential for an emergent narrative instead of a pre-written plot and player agency.

My experience as a “professional monster”

As a former US Army Soldier, the idea that monsters might wait in ambush using just their best strengths and abilities against the player character’s weakest points runs contrary to my own experience.

I was taught both in Basic Training and Infantry School at Ft. Benning GA to not merely attack enemies when making contact with them. When gaining sight of the enemy, it was far more important to “define the battlefield” through information, so that the larger effort of US Forces could gain dominance through maneuver, terrain, firepower etc. When encountering the enemy unexpectedly, it’s not as though we know the full composition of their forces, acting on little information invites fatal disaster. Later in Intel Analyst school I was trained to piece together fragments of information to help “define the battlefield” for Commanders in order to help them in making decisions. Even then, it wasn’t always clear. We were often wrong, and didn’t know perfectly what we were doing.

Even using our greater strengths, we would have complications and issues that made the management of violence incredibly wild and unpredictable. Weapons would jam, sattelite technology would fail, and of course the ever present human error was there, “Murphy”. We might have superior firepower, and people would not clean their weapons. We might have superior mobility, and people would fail to PMCS (check the oil and tires etc.) their vehicles. We might have superior communications and command and control (C2) and idiot Commanders would squander it through poor judgment and even failure of character at the critical moment.

Often times we would succeed against an enemy not because of our own superior knowledge or abilities, on that account we would sometimes fumble, but mercifully, the enemy would fumble harder. They themselves would be uncertain of our capabilities. They would make wrong moves and decisions on poor assumptions. They themselves are beset by concerns about morale, disease, weather, and the secret weaknesses of their forces that they enter the dire gambit of battle knowing is a liability.

To return to the topic of Old School Renaissance games, there is no imperative (unlike in D&D 5e) to ensure encounters are both balanced and challenging. Having elements of the world tied to it’s own ecosystem and truths are challenging enough. Perhaps more importantly, this is more interesting and fun.

OSR games lend themselves to this sense of a living and breathing world that players can make choices in and succeed or fail without the interference of a Dungeon Master or even game rules trying to “balance” matters for or against them. Best of all, this means the players are really running the show by their own choices and agency (and it’s much easier to be an OSR referee when all you have to do is honestly present the world.)

Top to bottom design for emergent narratives

From the top-down, referees consider what Gary Gygax called the “campaign milieu”. The campaign milieu includes the “fictional soup” or “tea” that mixes together the fictional elements in a world that has an internal logic. While Gygax emphasizes that there should be set “truths” and hard elements laid down for the world to be logical, it’s most important for a referee to understand the fiction the rules are based on more than things like random monster tables and weather generation, which arise after the fact from the fiction.

“It is no exaggeration to state that the fantasy world builds itself, almost as if the milieu actually takes on a life and reality of its own. This is not to say that an occult power takes over. It is simply that the interaction of judge and players shapes the bare bones of the initial creation into something far larger. It becomes fleshed out, and adventuring breathes life into a make believe world.”

-”The Campaign” page 87 Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Dungeon Master’s Guide 1979 Gary Gygax

“A Key Concept That You Need to Run OSR Games!” - Travis Miller Aug 2022

This “Open system” of mixed fictional expectations can be the primary tool for referees on what should appear on random monster tables and whether or not there should be a Thieves Guild in a particular city.

Gary Gygax suggests that the placement of threats, factions, monsters etc. should have a logic tied to this open system and the truth of it’s fiction.

“In general the monster population will be in its habitat for a logical reason. The environment suits the creatures, and the whole is in balance. Certain areas will be filled with nasty things due to the efforts of some character to protect his or her stronghold, due to the influence of some powerful evil or good force, and so on. Except in the latter case, when adventurers (your player characters, their henchmen characters, and hirelings) move into an area and begin to slaughter the creatures therein, it will become devoid of monsters.”

-”The Campaign” page 91 Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Dungeon Master’s Guide 1979 Gary Gygax

Gary Gygax goes on to suggest how monsters might migrate, be depopulated, repopulate, how adventurers may either migrate or set up roots and become the local establishment.

Whatever happens, this underlying agreed upon fiction, the open system the “campaign milieu”, the truth of the world, is the authority upon which monsters appear, which monsters and where, as well as how they will act when encountering player characters. The actions of monsters are divorced from player characters and their abilities, and the immersion breaking and contrived storytelling of a Dungeon Master placing monsters facing the player characters to “challenge them”.

Bottom to top design for emergent narratives

From the “bottom up” the Monsters also don’t know what they are doing. And I believe this is one of the keys to allowing a narrative to emerge rather than being written in.

One of the failures of modern RPG adventure design is that they tell you what to do and where to go or try to anticipate player actions. They have a lot of implied assumptions, especially trying to “guess” what players might do, and then it’s left for Dungeon Masters to try and bring these narrative elements into harmony. New Dungeon Masters look at adventure paths and modules and think this is easier to lean on, that they lack skill and that is why the difficulty is so high.

An excerpt from “Journeys Through the Radiant Citadel” - Wizards of the Coast, 2022. One of the most poorly rated D&D adventures of our time, after nearly a decade of poor adventure design tradition by the mainstream. It uses the same “adventure path” formula for Dungeon Masters, providing a single hook, expecting player characters to take the hook, then head to he next location and story beat. It uses language very often like, “If the Characters…” to anticipate their moves.

The truth is actually the opposite. Already arriving at what is going on in the adventure and then trying to find ways to weave them together with both player character backstories, a truth to the world and then the wildcard of player choices is a steep hill to climb indeed (not to mention those pesky dice rolls). It starts at the end and then tries to reconstruct the whole body of work to the beginning. The truth is the beginning is the hard part, and the human mind is an amazing machine for filling in the gaps. What we need are the various elements of the world, and then creative reason naturally arises from these elements to do the work for us. We need the “who, what, when, and where” and our minds will naturally tell us the “why” and “how.”

In Matt Finch’s recently re-released masterpiece “Tome of Adventure Design” he uses evocative phrases and words in the margins of the text and then presents paradigms and patterns to allow people to quickly produce adventures rather than giving them an adventure and having the world-builder work back to a truth.

“…a human trait known as apophenia — our ability to look at a set of unrelated things and find a pattern in them. The obvious example is the way people perceive shapes and pictures in a mass of clouds…It’s not exactly the same as creativity — creativity involves generating novel and quality ideas, whereas apophenia creates patterns that might be creative…”

Foreward to the Revised Edition - Tome of Adventure Design Revsied, Matt Finch 2022

This is the key in old school gaming to presenting a realistic world with very little effort on the part of the referee. It’s fun and easy. Our brains are made to do this.

In Old School Essentials (same as Dungeons and Dragons Basic Set, 1981) procedures help to provide the “ecosystem” locally for what is going on with monsters. It does so in a single page allowing Referees to determine the who, what, when, and where within moments. It remains only for the referee to determine the “how” and “why.” This is suprisingly easy to do when you already understand your “campaign milieu” and then are given everything except the “how” and “why.”

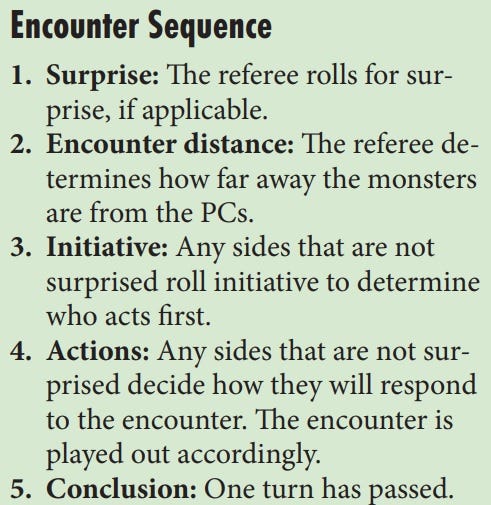

The “Encounter Sequence” page 124, Old School Essentials - Classic Fantasy Rules Tome, Necrotic Gnome 2020.

See the “Encounter Sequence” for a Dungeon above? Taken by itself it gives you no information for your game, it doesn’t interact with the “campaign milieu”, “open system” or “fictional soup” of the world to become a narrative yet. But let’s go ahead and run this together adding together a “how” and a “why” at the end of each:

Encountering what? The Referee has determined that in the Temple of the Frog God there are Lizardmen guarding an ancient unholy shrine using Page 140 of the Old School Essentials Classic Fantasy Tome, any other tool or simply their imagination.

They create a table of 6 monster encounters including 2D4 Lizardmen appearing. During the dungeon procedure after 20 minutes or two turns, the Referee rolls a “1” on a D6 indicating a random monsters appear relative to the fiction and the dungeon’s ecosystem.

Surprise - Are either side surprised? Each side rolls a D6 and the Lizardmen roll a “1” indicating they are surprised.

WHY - The Referee determines that the Lizardmen are occupied with some unholy ritual, making inhuman croaking noises to supplicate to their amphibion deity. This noise they are making and focus has made them unaware of someone approaching.

Encounter Distance - Where are they and how far? The Referee rolls 2D6 and rolls a “12” indicating they are 120 feet away. Since the room around them is only 30 feet long, and the players weren’t “surprised” the Lizardmen are in another chamber.

HOW: Using the fiction of the world the Referee determines that since they are occupied with an unholy ritual and can be heard 120 feet away, the sounds of their croaking must be echoing down a nearby hall from the refuse pit where the Grey Ooze is down an ancient well. The Grey Ooze in the ancient well is an element of the fiction designed in advance when the referee created the dungeon. The Lizardmen are part of the ecosystem of the dungeon, but weren’t orginally planned for this room. This creates a new fictional tension, as the Grey Ooze may or may not become involved later.

Initiative - Because the Lizardmen are surprised, the players are able to act after the Referee describes the situation.

Actions - If the Lizardmen become aware of the players, or if they hadn’t been surprised, the referee might roll 2D6 for a reaction roll. Either way you might choose to determine their disposition.

WHY - On a result of an “11” the referee determines that because of the fiction surrounding the game so far, knowing that a group of human cultists work for the Froghemoth and the player characters had to slide through a muddy sludge to arrive at the site, it makes sense that the Lizardmen simply regard the player characters as lowly human cultists. Humans are merely food/pets after all, and they look the same smooth, lumpy, nondescript way for the most part to the Lizardmen.

Notice: The reaction of the Lizardmen is facing the world and their place in it, not the player characters and their abilities or the expectation of a tactical combat.

As part of Step 4, none of these truths of the world are given as exposition but the Referee now has everything they need to provide an interesting situation.

A group of Froghemoth obedient Lizardmen cultists sulk in the dark around an unholy altar, unaware of the player characters nearby. If they see them, they’ll likely regard them as fellow cultists (or food) unless they are hostile.

With this information arising naturally from the combination of the world and player choices so far rather than being pre-written by an adventure designer, the Referee can describe their situation:

“After sliding down the thick, sticky mud you are in the dark for a moment as you clamber to re-light a torch. For a moment it seems as if it won’t light but thankfully a weak flame sputters at the end of the rugged handle. The cavern chamber here is about 30 feet long and 20 feet wide, in the flickering torchligh your companions are covered in muck head to toe. Somewhere in the distance down a cavern tunnel you can hear echoing the sound of guttural croaking noises, combined into some kind of unholy chant.”

Now, “What do you do?”

What will the player characters decide? Do they get caught? If so, what will they do when it’s clear they are being invited into the ritual? What about the Grey Ooze at the bottom of the shaft? For the Referee, this doesn’t matter. They are an impartial arbiter, combining the truth of their campaign milieu with the dungeon procedure and then presenting this to the players to make their own choice.

The story is whatever arises out of this situation and the choices the players make. And the referee has had to prepare very little at all for all of this to come together. They story will be the player’s story, not the Referee’s pre-written one, and it will be much more interesting and memorable.

In Summary:

The Monsters do not, in fact, know what they are doing

This is because they aren’t simply existing in the world for the sake of the player characters but act according to their own logic and concerns in the world. They are very often unlikely even aware of the existence of the player characters at all. Even if they are it is very unlikely that they have a clear view of what the player characters intentions and capabilities are.

Designing a world with central truths, applying procedures that create a framework of choices and then reacting to the choices of players is actually an easier and harmonious way of running RPGs unlike modern style adventures where DM’s are told to maintain story beats, already have a direction for the story then attempt to weave together the disparate elements of player character backstories, the dice and player choices.

Apophenia is a powerful tool of our mind. Being given the beginning; the who, what, when, and where, is all we need to piece together the how and why.

The story that arises from the table is more interesting than one written in advance

I think you do a disservice to Ammann and his approach. The point is simply that (particularly in 5e) monsters are designated as having specific abilities. Those abilities have to be either instinct or training. Whichever they are, it makes sense for the monsters to rely on them. If goblins can attack and then hide as a special thing, they should be looking for opportunities to do that. The goal is actually to make the world more naturalistic. One of the things Ammann emphasizes over and over is that monsters (mostly) aren't murder machines, and the GM should bear that in mind when deciding how a monster behaves. If a monster's ability suggests ambush predator (e.g. special attack jumping out of a tree) then consider how ambush predators behave in the real world when running it. Have it attack stragglers, have it break off and flee if it can if the ambush doesn't work and it finds itself in a real fight, don't have it pursue runners if it's secured its meal, etc.

What are they doing?

1. Sleeping (automatic surprised)

2. playing games/talking among themselves (players have advantage on perception checks)

3. drinking/carousing (disadvantage on perception checks)

4. Eating/cooking/preparing a meal.

5. Searching the area/ looking around (advantage on perception checks)

6. They see you and you see them so roll initiative, oops.